Introduction

By Jean-Jacques Pauvert

The publication of Story of O was one of those rare adventures in publishing, paradoxically both disappointing and exhilarating. It cannot be summed up in one date – the publication date – but instead covers a period of over two decades.

Story of O came out in June 1954 as the work of an author named Pauline Réage, with a preface by Jean Paulhan. It was a time when freedom of expression, a precious tradition in France, was at its lowest ebb. Court proceedings taken against me in 1947 over the publication of the Marquis de Sade were dragging on, due to newly passed hypocritical laws that accumulated charges.

I had been so enthralled by the manuscript of Pauline Réage, however, that I had inserted a little pamphlet in the book which claimed: “We guarantee that Story of O will mark a date in the history of all literature.”

I was 28 years old, and although not without professional experience (I had published my first book at 19), it would be fair to say that I was still somewhat naïve. Actually, I was convinced that Story of O was going to revolutionize the book trade, that I would sell hundreds of thousands of copies across the world, and that moral attitudes would change overnight. The audacity of this novel seemed to me to be liberating rather than provocative. I perceived the promise of a new freedom. And I expected to cause a shock.

As things turned out the shock, if anything at all, was more of a dull thud and remained almost totally unnoticed.

Only three reviews appeared in the press – albeit two of them very significant. The third one, published first, consisted of a short article in a weekly called Dimanche matin – now extinct – by Claude Elsen (author of Homo eroticus published by Gallimard).

“All in all,” wrote Claude Elsen, “far from belonging to the licentious genre, Story of O is close to those legends or those epic poems which celebrate l’amour fou, or the ‘Song of Songs’, or the romance of Tristan and Isolde” …

This was quite a good start. But in the Nouvelle Revu française of 1 May 1955, Georges Bataille went further:

“… The eroticism found in Story of O also contains the impossible aspect of eroticism. To accept eroticism means to accept the impossible – or more to the point, to accept that desiring the impossible constitutes eroticism. O’s paradox is similar to that of the visionary who dies of not dying, or to martyrdom that consists of compassion shown by the torturer to the victim. This book reaches beyond the word, breaks out of its own bonds, dispels any fascination for eroticism by revealing the greater fascination exerted by the impossible. What is impossible here is not only death, but total and absolute solitude …”

A month later Critique, a confidential but influential magazine, published a review by André Pieyre de Mandiargues. It was as long as Bataille’s article. Under the superb heading, “Irons, fire and darkness in the soul,” Pieyre de Mandiargues pointed out that “this novel, which is anything but vulgar, appears to borrow from publications generally classified as crudely pornographic. This may seem surprising, yet the author is right. For did not Julien Gracq state, in his preface to Au Château d’Argol, that the outcome of all battles, whether victory or defeat, is determined by identical tactics? In his own work, Gracq deliberately restricted his instruments of terror to the kind found in the Gothic novels of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Similarly, Réage exploits the well-tried recipes used in the hundred or more clandestine books distributed under the counter. … And when an author like Réage – who, as I said earlier, constructs a story with the art of a very great writer – chooses to dispense with any fantasy in the details, it is safe to assume that she does so out of pride, because she aims to excel using only ordinary means…”

However, in spite of recommendations from those two great names (as well as from Jean Paulhan), the few who read Story of O reacted in a way that was, for me, totally unexpected. Of course, it must be said that neither the Journal du dimanche, nor the Nouvelle Revu française, nor Critique, were very widely read. Furthermore, in the context of the times, these people, who were well-informed, could have but one reaction: they were terrified.

In short, what I had failed to realize was that the book trade was not ready to handle this kind of literature. Everybody was talking about Bonjour tristess, by Françoise Sagan, a novel which had come out at the same time and was regarded as scandalous. But there was no mention of Story of O anywhere, except by word-of-mouth. Booksellers who had shown some interest in the book were unanimous: it would be banned.

Indeed, the police were getting nervous. Story of O had been the subject of an inquiry by one of the book (censorship) commissions set up by the Department of the Interior. The ruling of the commission was unequivocal:

“After hearing the report of Mr. … and having duly considered the matter:

“In view of the fact that this book, published by Jean-Jacques Pauvert, relates the adventures of a young woman who, in order to please her lover, submits to every erotic whim and ill-treatment

“In view of the fact that this book is violently and consciously immoral, that it contains scenes of debauch between two or more people, as well as scenes of sexual abuse, and contains a seedbed of abhorrent and reprehensible behavior, thereby constituting an outrage to public decency

“The commission concludes that proceedings should be taken against it.”

As it happened, no proceedings were taken. I was interrogated, but preserved the author’s anonymity, while Jean Paulhan delighted in confusing the police with improbable leads. Moreover, pressure from mysterious quarters was brought to bear in favour of the work.

Booksellers were nonetheless afraid, and less than 2,000 copies of Story of O were sold in its first year.

On the other hand, it turned out that during that year each copy was read by at least ten to twenty people. Story of O was passed discreetly from hand to hand. The book was pursuing its career underground, and sales rose every month. Some years later, the author of Emmanuelle pointed to the profound impact Story of O had made:

“It is often said of someone who has experienced a certain event that ‘he or she was never the same again’. Well, this novel was precisely such an event in our lives. It has transformed us. We are marked by it, more lastingly and more deeply than the red-hot irons that branded O, who bears the stigmas in our name … Without Story of O, Emmanuelle may never have been born.

And so it was that I watched Story of O’s progress, year after year, silently winning over a thousand, two thousand, ten thousand new readers. The “sexual revolution” of the late 60s brought it to the summit of its success. In the United States, thanks to Barney Rossett, Publisher at Grove Press, it was an instant best seller. Little by little, Story of O became the most widely translated French novel in the world – just as I had predicted twenty years earlier. I had simply spoken too soon.

Finally, in 1975, Story of O was made into a film (the French weekly, L’Express, produced a memorable front cover to mark the occasion), consecrating the triumph of a book which, by then, had sold millions of copies.

To conclude, we must speak of the author, since the very fact that she was a woman – or was she? – has been for a long time the source of heated debate.

Two camps were irreconcilably opposed: on one side stood those who were absolutely certain from the first that the novel had been written by a woman; on the other, those who could not – and still cannot—bring themselves to accept that no man ever had a hand in it.

We know now, and have done for some time, that the woman who described how, “one evening … , instead of picking up a book before going to sleep, she curled up on her left side and, with a strong black pencil in her right hand [started on] the story she had promised to write,” was Dominique Aury, Editorial Secretary at the Nouvelle Revu française. And that she had worked practically on her own.

What matters most is that Story of O was written by a woman. There is no need for me to elaborate on the consequences. They were many and varied. For better or for worse.

What matters to me, today, is that this novel has preserved its suggestive powers intact to the point of inspiring a young woman of the new millennium to express her own fantasies.

Doris Kloster, whose unique talent lies in her subtle treatment of any subject, has worked hard, meticulously sticking to the text, to explore her own vision of Story of O through her art. Of course, being more practiced in the literary than in the visual medium, I cannot presume to judge the result. But I can attest to the extraordinary conscientiousness she showed in her endeavor to recreate a fantasy through her photography.

What new light will the Story of O, with its newly acquired dimension, be perceived by the present generations? We long to see.

But the fact that, almost fifty years on, Doris Kloster should have chosen Story of O to attend her on this vital journey into herself, proves that perhaps I was not altogether wrong, one day in 1954.

Jean-Jacques Pauvert

Paris, April 2000

Preface

Since its publication in 1954 in Paris, Story of O by Pauline Réage has never been out of print. This popular and psychologically profound work of erotic literature caused a sensation when it was released, and it still has the power to disgust and shock timid readers. It is a book that relates potent, forbidden fantasies that, even today, few people dare to think, speak of, or write.

The story involves a young, beautiful fashion photographer, O, who lives in Paris. As the novel opens, her lover, René, takes her to a château in Roissy. Here O is introduced into a world where women are subjugated, physically abused and turned into sexual slaves. O submits to René's wishes that she be imprisoned, whipped and made completely available to the desires of other men. After taking her from the château, René introduces O to Sir Stephen, a more severe and experienced sadist. Sir Stephen, in turn, passes O into the hands of Anne-Marie, the ruler over a household of naked women. And at every step in this systematic degradation, O finds deeper and deeper levels of sexual and psychological satisfaction. Near the end of the novel O wonders, "Would she ever dare to tell him that no pleasure, no joy, no figment of her imagination could ever compete with the happiness she felt at the way he used her with such utter freedom, at the notion that he could do anything with her, that there was no limit, no restriction in the manner with which, on her body, he might search for pleasure?"

The author, whose real name was Dominique Aury, created Story of O as a way to hold the interest of her long-time lover, critic and intellectual, Jean Paulhan. When Aury suggested she could write in a style that would impress and excite the man she feared might leave her, he expressed skepticism. Therefore Story of O is, on several levels, a woman's successful response to a man's challenge. When asked on one occasion "aren't these male fantasies?" Aury said "I don't know, all I can say is that they are honest fantasies."

Paulhan championed his lover's Story of O among literary scholars, and wrote the preface for the work. It was he who found the book's publisher: after the manuscript had been turned down by a number of other editors, Paulhan brought the work to Jean-Jacques Pauvert, a daring young publisher who had previously published the entire works of the Marquis de Sade. I am honored that Jean-Jacques has written the preface for my illustrated version of Story of O.

While my work in previous photo books has tended to be documentary in style, dealing with real life and real individuals, this book revels in pure fantasy. Creating the photographic representation of the most famous work of erotica has been a long-standing dream of mine. Story of O is both an esteemed work of literature and a primer in alternative sexuality. I considered the task of realizing Story of O in pictures to be both an honor and a great responsibility. I wanted to portray in detail the intense eroticism of the novel, yet somehow not restrict the vision brought by the story into the mind's eye of its myriad admirers throughout the world. It is appropriate that a woman undertook the visualization of this novel, written by a woman. The main character, O, is herself a photographer; and she is not simply submissive. Especially in her relationships with other women in the story, she often proves to be willful and manipulative.

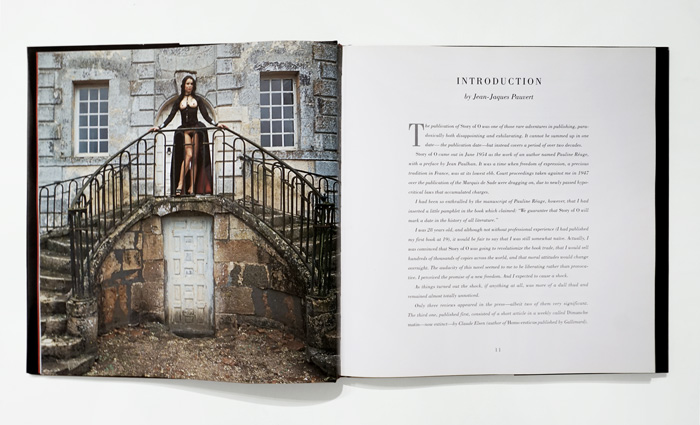

To me, Story of O is a timeless literary work, not a historical artifact. Therefore, this book of photographs does not attempt to recreate the original story in every detail. However, I did try, whenever possible, to match the characters, clothing, props and settings to the descriptions in the novel. I wanted to photograph the story in locations that evoke the mystery and fantasy that is the Story of O. The novel is set in Paris and its environs, the most romantic locale in the world, and the home of the Marquis de Sade.

Generations of artists have sought inspiration within the demi-monde of this great city. Degas, Toulouse-Lautrec, Manet, Zola and many others have come here and portrayed their fantasies of sexually available women. To infuse this book with romance and authenticity, I brought my models, crew and equipment to a number of settings in Paris, including the national monument and castle on the Îsle de la Citè, the Conciergerie, and châteaux in the Loire Valley, including the seventeenth-century fortress, Château de Saint-Loup.

In his preface to Story of O, Jean Paulhan writes that the book is dangerous because it marks the reader, and "leaves him not quite, or not at all, the same as he was before he read it." That was certainly the case for me, for I never had the same perceptions of sexuality after having read Story of O. The work rekindled deep and potent fantasies from a time when early glimmers of sexuality appeared to me only in dreams. I hope that by experiencing Story of O in a new way, through my book, readers may find new pathways where their imagination and memory can discover fresh resonances with Aury's original vision.

Doris Kloster

Paris, April 2000

![]()

© Copyright

Doris Kloster 2024

![]()